Game Trails

2021-04-14

Preface

The Civilian Climate Corps — a New Deal Era 'Civilian Conservation Corps' reinvented for the contemporary threat of climate change — is closer to reality than it ever has been. As of April 2021 the Biden Administration has made numerous announcements of its impending arrival and lawmakers have recently released a bill outlining its creation. While there are many logistical considerations at play for what the CCC will look like, it remains to be seen what the CCC will feel like. This story about a CCC program in Maine set several years into the future, attempts to do just this.

It seemed like her entire life had been about playing attention games. Sometimes this game was figurative, but oftentimes it was literal. Call it an escape, or maybe just an innocent preoccupation, she had always had a fondness for passing time with games on her phone. As a young child her parents were quick to give her an iPad during idle moments and like many other kids, she gravitated towards the type of games that scrubbed away the messy outside world. Over the years, this innocent escapism came to rest somewhere between a habit and an instinct. Now as a twenty year old in her third year of community college, she kept on bumping against the fact that her mind had been molded around the smooth geometries of mobile games.

Despite this pastime, a disinterest in competitiveness mixed with a gentle fondness for all living things led her to choose wildlife biology as her major. She had aspirations of becoming a vet or maybe even staff at a zoo, but she had never been that great at schoolwork and the realities of a faux meritocratic future beyond college scared her. Sometimes she found it easy to blame her casual smartphone addiction as the source of her academic malaise, although it was probably the case that this malaise extended far beyond school. After almost two decades of immersion in near frictionless digital spaces, sometimes she found it difficult to rectify the irrationality of just how thorny ‘real life’ seemed.

Upon completing her last finals that Junior year, she went back home to stay with her parents for the summer. Some of her classmates had set out on internships, but she didn’t have any such plans. Maybe the restaurant she had worked for the summer prior would hire her again. Although not the greatest pay, she enjoyed being able to pass free time between services on her phone.

It was a hot and muggy morning in her hometown Long Island suburb when she decided to take a walk to play one of her favorite games -- a popular augmented reality scavenger hunt app. The game used players' phones access to geographical data and a camera feed to create an environment that blurred the line between truth and fiction. In this in-between place, players searched for real world clues which led to virtual prizes. She had been one of the most prolific players in her area, consistently topping the regional leaderboards.

In the middle of this morning’s session she was greeted with a full screen ad, something not atypical. Her mind had subconsciously memorized the exact motions her thumb needed to take to exit the ad before she could even process it, but the rapid movement of her finger alongside the humidity of the air made the phone slip from her hand and fall onto a patch of grass beside her. As she picked it back up to inspect the screen for any cracks she broke from habit and started to read the contents of the ad.

At first it confused her. It showed an augmented reality game interface not dissimilar to the very one she had been playing. She thought it might have been a glitch but it was just clever marketing. The likeness quickly subverted her attention towards bold, red text in the middle of the ad. “Play. For Real.”, was superimposed over an image of a forest glowing green and gold. Without thinking much, she pressed the “Read more” button beneath.

The North Woods of Maine is a sparse place. It stands in stark contrast to the state’s coastal communities of the south where the water seems to wash ashore prosperity alongside a slew of vacationers latching on to it. Any point past a modest car ride from the coast quickly begins to feel primitive, even lonely. But like any other place that can be labeled as such, there is often more than meets the eye.

Beyond the rich cultural traditions of indigenous groups, including the Miꞌkmaq (Maliseet) and Pαnawαhpskewahki (Penobscot), Maine’s northern woods are in fact full of life. Anyone who actually bothers to make the journey North will tell you this. While human presence might seem fragmented, Northern Maine is a region of abundant life. Conifer forests extend for swaths as big as entire states, only to be broken up by pristinely clean dotted lakes and waterways. The flora and fauna of these isolated regions is by and large it’s greatest source of wealth. Often this comes from the constant balancing act between direct harvest and regeneration of timber. Not far behind is the wealth generated from touristic spectacle.

One gets a sense that if not for the slightly flashier, more hospitable landscapes of the west, Maine would preside as the crown jewel of America's outdoor spaces. For those who have had the pleasure of spending time in Acadia or the Lakes Region, they probably prefer the lack of attention relative to Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the like. To call any of these sacred Maine landmarks ‘lesser’ would be farcical.

Tragically, the lack of human presence in Maine’s North Woods has not freed it from human impact. Namely, climate change has begun to harm the health of this ecosystem. This was a threat not entirely discrete nor surprising. Ever since the 2010s, small but extreme mean temperature deviations had caused concern that what scientists had warned about for decades prior was coming true.

In Maine’s North Woods, weather anomalies weren’t the only hint that underlying climatic shifts were well underway. Warmer winters had led to increasingly habitable conditions for a particular parasite — the moose tick — which as its name implies, loves feeding on the towering mammal that resides in Maine in larger numbers than any other state besides Alaska. The ticks, which were previously kept in check by Maine’s brutally icy winters, were now exploding in population. It was not uncommon to find hundreds if not thousands latched into a single moose come winter when they feast. You didn’t even need to find a moose to confirm this. Desperate for relief from the fatal anemia that the ticks could bring on, moose would scratch their torsos up against tree trunks. What followed could be a scene from a horror movie. Streaks of blood spread upon the pale grey bark of birch trees and splattered over the blank white snow. A stark visual reminder that the climate is indeed changing.

For the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, an expansive park located east of Mount Katahdin that had been newly established in 2016 after a donation from the Burts Bees chapstick fortune, climate change was a principal concern. The Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife had been remotely monitoring both moose and moose tick populations and as of 2024 began to be worried about ecosystem collapse. What was originally a stable community of approximately 800 specimens as of the park’s creation, was estimated to be 500 less than a decade later. The Department’s wildlife biologists worried that parabolic dieoff would mean that this number was even lower in reality, but data sampling in such a remote area was costly and difficult.

For the Brooklyn tech startup, Fieldr, positive impact was paramount. At least this is what the company’s marketing materials reminded the public of at every opportunity. Started by three Ivy League-educated twenty year-olds in 2022, Fieldr saw a vision of the future where benevolent tech corporations of the 2020s were the answer to malevolent tech corporations of the 2010s. The only problem was that the company didn’t quite have a public product. For over two years the small team had been working on a new type of nature-based augmented reality game that could be both fun, enriching, educational, and altruistic. In pitch meetings, Fieldr’s CEO described their app concept as “broccoli that tastes like ice cream.” This alchemy didn’t work that well on investors though. Despite the cash-laden and guilt-ridden reputations of Fieldr’s target angel investors, no one took the bait on a product that was merely in prototype phase, no matter how impactful it advertised itself as being.

Destitute and contemplating life beyond The Startup, Fieldr’s founders decided to make a hail mary play before calling it quits. An opportunity had arrived at their doorstep via a Columbia classmate who worked in Washington. The Biden administration, now in its second term, was starting to get serious about allocating funds to kick start what it was calling the Civilian Climate Corps. The CCC was an intentional reference to the New Deal-era CCC, the Civilian Conservation Corps. The original CCC employed young men from around the country to build public infrastructure like dams, roads, parks, and trails. The reinvented CCC would also be focused on employing young people (not just boys) to build on public infrastructure, as long as it had some relevance towards climate change.

Fieldr’s founders got wind of a Request for Proposal put out by the EPA alongside Maine’s Dept. of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. The RFP asked for a way to assemble a corps of CCC members in the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Being still relatively young, the park was in need of straightforward amenities like trails and bathrooms. In addition the RFP commented on the park's recent issues with gathering data on moose ticks. Putting two and two together, Fieldr made a bid to capture CCC grant funding through a white label version of their augmented reality app that hypothetically could solve the agencies’ data acquisition problem.

The sheen of Fieldr’s proposal relative to other more generic submissions landed them the deal. With a windfall of federal grant funds they were able to hire developers to finish their app. The end product was a game that offered players an addictive reward system for photographing flora and fauna in real life. The idea was to use CCC members to closely monitor a tract of land in Katahdin Woods and Waters as a means to get better data on the overall population health of moose in Maine’s woods. Instead of the meticulous training and field work that traditional conversation biology required, Fieldr would use young adults from everyday backgrounds to carry out a more fun, affordable, and potentially efficient form of observation. At least that was the idea. Now all that remained was finding its users.

The drive up to Katahdin Woods and Waters from Long Island was just far enough to feel like she had firmly left wherever she had been. She was told that there would be almost thirty other people her age arriving at camp that night alongside her. The prospect of icebreaking with strangers she would be living with for the next two months made her slightly nauseous, as did the idea of spending that entire time in a tent.

Before she could think about sleeping bags she was thinking about what the hell she was doing joining the Civilian Climate Corps. No rationalization was able to make the plan she had now embarked on not feel completely insane. Only a month ago she had been planning on waiting tables at a restaurant in her hometown. Now she was a federal employee crusading for a cause she wasn’t even that committed too.

Like virtually every other person her age that she knew, she believed in climate change. But she never felt much of a connection to it. It had been something always floating around in the background of her life. Just as she understood it was a big deal, she reckoned that only people who were also a big deal would be the ones taking care of it.

It wasn’t just the app company's clever marketing that made her sign up for Fieldr’s pilot. She would be the first to admit that the idea of making money playing a game was appealing, but the decision to jump on the opportunity was ultimately spawned by something else from within her. What exactly this new energy was hadn’t revealed itself yet. It was all so strange, almost comical. All she knew was that she had been presented with a fork in her life and for the first time in possibly forever she took the path that felt like the most precarious. Just because.

Maybe it was her sense of compassion unfurling into newfound bravery that had been pulling the levers. Beyond being a sort of game, the opportunity to be doing work that had a moral bend to it appealed to her. At the very least, reading about the plight of Maine’s moose population had tugged her heart strings. At the very most, perhaps it was the case that she was beginning to feel a sense of agency towards the climate crisis. No matter how strange and spontaneous it materialized as, the corps represented a chance to awaken a part of her that had begun to be buried in layers of self-centeredness over the years.

It was a dirt road that eventually led to her new home. When she opened her door and stepped out of her car, that first breath of Maine air was shockingly clean. She realized she hadn’t even known what fresh air really smelled like until then. It was rich with the scent of pine trees and something else sweet she couldn’t place her finger on. The second breath wasn’t as refreshing. She had accidentally inhaled a black fly, which were so abundant in early July in Maine that they might as well be considered ambient. Like choking on your own spit on a first date, she let out a few unconvincing discreet coughs, hoping that judging eyes hadn’t noticed her. Thankfully nobody seemed to be watching.

The first person to speak at the welcoming ceremony was one of her corps leaders, a scruffy looking Mainer in his thirties who had spent his professional life bouncing around whatever gig gave him closest proximity to the outdoors. Over the next two months, she would come to view him as both an inspiration and tragedy for what happens when you break free from the rules of careerism. In his remarks he earnestly spoke about the importance of protected land, and what the future of climate change had in store for Katahdin Woods and Waters. He also spoke about the significance of the corps. “The strangers sitting next to you might very well end up being some of your life’s closest friends,” he said. She rolled her eyes at this, but was internally hopeful towards the idea.

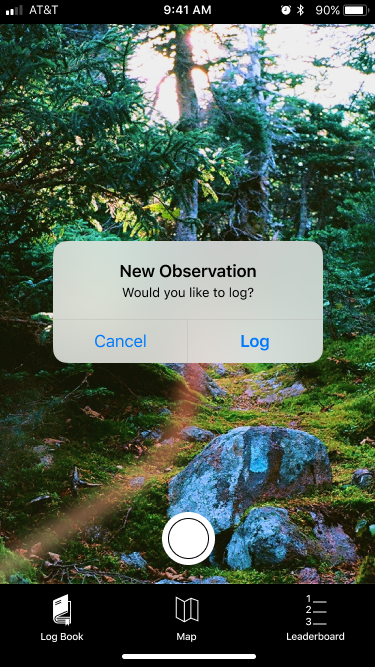

One of the Fieldr cofounders had drove up to Maine for the weekend to ensure the smooth launch of the pilot they had so much riding on. He was also given an opportunity to speak at the group orientation. His remarks noticeably drifted away from solidarity and stewardship. Some of this had to do with the logistical nature of his presentation. He went to great lengths explaining how the group would use Fieldr, its various menus and interfaces, as well as how the wildlife observation process works. In a nutshell, the corps members would individually set off on daily hikes on and off trail, taking pictures of literally anything that was alive. A set of rotating ‘daily challenges’ alongside a machine learning observation scoring system was used to incentivize unique sightings. More points for select and rarer specimens hypothetically pushed corps members to document a wider range of the park’s ecosystem. Being the central focus of the pilot’s underlying study, the moose population was particularly weighted as the most valuable encounter to capture. Gameplay was further enhanced by an augmented reality layer placed over a user's smartphone camera feed that created glowing trails and floating objects in the backcountry where there otherwise would be nothing. The entire packaged experience was almost suspiciously slick.

As he arrived at the end of his briefing, the cofounder told the crowd that there was “one more thing” he needed to mention. Fieldr had decided to up the stakes for the app by turning it into a bonafide competition. In addition to the standard CCC stipend each corps member would be receiving for their two months of work, the app would reward top players off an in-game leaderboard. Biweekly prizes of $1,000 were to be given to the top three scoring players during that period. More notably, the overall top scorer for the two months would receive $10,000. Audible murmurs could be heard in the crowd when the cofounder announced this. Suddenly the corps leader’s words about solidarity and friendship for life started to ring slightly hollow. If history has proven anything it’s that it’s difficult to be friends with someone you are competing for finite natural resources with.

After a round of small talk around the fire the corps got ready for bed and headed towards their respective tents. She shared hers with two other girls, one from Southern California and another from New Hampshire. They seemed nice enough. Sliding onto her cot, she felt her body, still stiff from the drive, sink against the taut canvas. It wasn’t nearly as comfortable as her direct-to-consumer foam mattress from back home, but she still fell asleep right away. In the morning the game would begin.

It was the first week of September. Sixty days in the Maine wilderness has passed since the Katahdin Woods and Waters Civilian Climate Corps embarked on their assignment cataloguing species via a smartphone application called Fieldr. The experience had been challenging, profound, and insightful for most of the corps. In a day it would be all over.

The girl from Long Island had undergone a transformation not unexpected from such a passage. She had learned a tremendous amount about the woods and its inhabitants. She herself had evolved from visitor to inhabitant. She could navigate on game trails and identity game tracks. She had an intuitive sense for the rise and fall of the day, the exact arc of a cool morning unraveling into a balmy afternoon. She had learned of the Eastern Pines near camp that harbored King Boletes two days after a late summer thunderstorm. She knew the different calls of each of the mating pairs of Loons that lived on the nearby lake. At dusk, their melodic cries sewed in her both a sense of peace and impermanence. She felt, saw, heard, that summer was quickly coming to a close.

It should be noted that the girl had not changed on any fundamental level. She was still the same person, the same girl from Long Island that loved playing games on her phone; the only difference was that she had been lifted into a new setting that surfaced the parts of her concealed by life back home. She had always loved animals; she had always enjoyed exploring. It just seemed like normal life had never afforded her the opportunity to do these things in such an unencumbered way. For the past two months it had been her only occupation.

Her fundamental sameness was further highlighted by the fact that much of the girl’s newfound forest vernacular was a product of having her smartphone on her at all times. Her time in the woods contradicted the gospel of tech minimalism that suggested the only way to experience nature profoundly was to do so through direct perception. Ironically, the only way she had come to learn so much about the flora and fauna around her in such a short time was through the interface layer of the Fieldr app, which promptly gave her any taxonomic information she could desire. Did this filter cheapen the profundity of the experience or did it concentrate it?

This was the question that tumbled around her head the night before the corps was all set to pack up their things and head back home. She was also thinking about the corps leader’s promise of friendship that he made on their first night. She had indeed made close friends in nearly every single corps member at camp, but she also felt that there was still an unavoidable rift between her and her cohort. The simple answer for this was money and competition. Almost immediately at the start of their documentation period, the corps members had taken the pursuit of prize earnings seriously. In passing moments between meals and chores, conversation almost always reverted back to the leaderboard. The top three observationalists of a given split loved to flaunt their exclusive in-app avatar skins that Fieldr rewarded them with. This isn’t even to mention the clamoring effect the cash prizes had on everyone, something that had come to a head on the eve of the final tabulation of player observation points. Like a low budget reality show, the chit chat around camp on their final night had been about who would be going home with the big prize tomorrow. She was secretly relieved to be ranked firmly in the middle of the pack and thus not in contention. She wasn’t looking for any drama.

The girl was not so stoic as to be completely free from the thirst that a $10k prize generated. She had bills to pay, and like many kids her age, a sizable amount of student loans. But she wasn't so stricken by greed to see the tainting effect this had on the broader principles of the CCC. While she had learned a lot about the woods, she still felt like the ‘climate crisis’ was an enigma. Only infrequently had her and corps members actually talked about it, and when they did it was always in the form of platitudes and broad strokes. She couldn’t quite sense climate change the same way she had learned to sense the forest around her.

There was one clear sign of climate change in Katahdin Woods and Waters though. The parasitic moose tick, which was the original impetus for their corps project, had commonly found its way onto corps members who were frequently scurrying in tall brush looking for observations. A nightly ritual the group had developed was peer tick checks, one of the few acts of mutual care that actually brought the crew closer together. Despite how common the ticks were, the moose that the Dept. of Wildlife and Inland Fisheries tasked them with documenting had rarely shown themselves. Only four corps members throughout the entire summer had made observations, something that they were quick to brag about considering this high scoring sighting almost always placed them instantly at the top of the leaderboard.

Sitting on her cot in the dark, the girl scrolled through her final list of Fieldr observations. She was already feeling nostalgic about the last two months as she rehashed the memories associated with each of her logs. She thought back to her car ride to Maine and that original feeling of uneasiness that had accompanied her spontaneous decision to join the corps. Now that she had been traveling down that fork in the road and it was quickly coming to an end, her anxiety wasn’t of an expanding decision tree. It was of its collapse.

She let out a deep exhale, her breath visible against the blue light of her phone in the now-cold, early fall night air. The cot hadn’t grown any more comfortable. Usually she was too tired from the day’s events to care, but tonight it kept her from falling asleep. She resolved to take a quick stroll to try and tire herself out. Be it her familiarity with the trails surrounding camp or the practically full moon that night, she left her headlamp and just grabbed her jacket and phone.

There was an undeniable peace in the forest that night. The moon cast pale shadows of frilled ferns over the rocky trail. As her eyes adjusted to the darkness, the tapestry of a dazzling starry sky gradually materialized. There were many things in these woods she had grown accustomed to yet still floored her with their beauty. The night sky a hundred miles away from any city of modest size was chief among the repeatedly sublime.

After walking for ten or so minutes she felt her anxieties begin to subside. A patch of clouds shifted in the sky and began to cover up the moon. The forest grew dark again. She took that as a signal to head back to bed, turning around towards camp and flipping on her phone’s flashlight to compensate for the onset darkness. Several minutes into her return journey, her phone angrily chimed, letting her know that the battery was on 10%. The aging iPhone that Fieldr had given her already had poor battery life, and the cold air that night wasn’t helping things. Since she was so familiar with the arterial trail she was on, she decided to navigate in the dark to save the remaining battery.

Several more minutes of walking and she began to sense something was wrong. She should have been back at camp by that point. Stopping to quickly turn her phone’s light back on and inspect her surroundings, she realized that she was not on the trail she thought she was. Her heart rate quickened. “Relax,” she told herself. “You probably just made a wrong turn when turned around.” Her phone beeped again. 5% now. Again, her heart rate quickened.

The girl felt humbled that her confidence in the geography around camp had suddenly backfired. Still, she tried not to panic. She hadn’t been walking for very long in the first place so there was no way she was too far off course. Taking a deep breath, she paused to take in her surroundings in hopes of reorienting herself. She placed her phone back in her pocket to preserve whatever precious battery was remaining. Looking towards the distance, she noticed that the moon was still shining in patches further down an offshoot trail. Instinctively, she followed the light.

Like a mirage, every time she got closer to the moonlight, it seemed to vanish towards a point further down the trail. Teasing as this was, the humor of it wasn’t lost on her. After multiple rounds of being led further into darkness by way of light, she actually began to relax. At this point she had completely acknowledged being lost, which provided a sort of fatalistic relief. Her phone wouldn't make it much longer, so she supposed her getting back to camp was now in the moon’s hands.

Approximately fifty feet in front of her she saw the moon glint off a white form separate from the outlined branches and boulders that dominated the forest’s horizon. She thought she recognized the oblong shape as a familiar trail marker that could finally lead her back to camp and headed in its direction. Once again though the shifting skies made her lose track of it as she got closer. She slowed her steps, patiently waiting for the clouds to allow in moonlight that would illuminate the blaze. Nothing showed. And then, all of the sudden, everything.

A deep, resonating thump, followed by a sharp rustle came directly from where she thought the blaze was. The noise wasn’t loud, but pierced through the otherwise silent night. Her mind began to scream with fear, but she didn’t move a muscle, didn’t make a peep. She just stood there and stared into the void. And then, it revealed itself. The clouds had departed one final time, giving way to a beam on moonlight that struck a gargantuan figure standing only ten feet away from her.

She was face to face with a creature that made her question base reality. Surely she was dreaming. Maybe these past two months had actually all been one prolonged dream. But there was a pressing tangibility of the scene that told her otherwise. The thing looked positively alien yet at once familiar. As her shock quickly wore away she connected the dots. What she was staring at was an albino moose.

The bull must have been 600 pounds. Its color palette was perfectly inverted from the deep browns she expected of the animal. She had actually heard stories about this exact moose from her corps leader. It was rumored to live in the park boundaries but hadn’t been seen in over a decade. She despised that she remembered this so quickly but she also recalled her corps leader saying that they programmed a special rule into the Fieldr database for rare sightings such as this one. If she were to capture a photograph of the encounter she would instantly get enough points to move her to first place in the competition.

She felt the outline of her phone in her right pocket, knowing that at this point in the night there was probably only just enough battery to open the app and take her picture. She hesitated grabbing it, fearing that any movement on her behalf might startle the moose. Even outside of mating season they were known to be one of more dangerous animals in the region. Slowly she reached down and felt the cool glass screen in her pocket. Her shaking, clammy fingers clumsily tapped the phone to wake it up. The battery monitor read three percent. Opening the Fieldr app, she waited for the home screen to load. She normally found the smiling squirrel mascot, which lived on the loading screen, cute, but at the moment it seemed to only be mocking her. Another percentage point was taken off the remaining battery.

Finally the camera loaded, and she framed the moose, which remarkably had kept just as still as she had throughout the entire process. The viewfinder was black — she would have to wait until the camera’s flash fired to see if she lined up the shot properly. Quickly and unconsciously, she pressed the capture button. The flash stuttered, then flared out. She blinked and in that split second her brain took a photograph of its own. She saw the entire contour of the animal and its surroundings, its beady eyes glowing bright yellow, its soft white fur swirling and rippled.

Her eyes opened and fixed to the screen to confirm the shot. She saw nothing. The phone had died. Once more, all that was there was the moose, the forest, the moonlight, the darkness, and the decision she faced of what to do next.

Notes and Acknowledgements

Thanks to Toby Shorin, Kei Kreutler, Aaron Lewis, Lukas Winkler Prins, James Ayres, and the rest of the Blogger Peer Review and Rainforest Cafe crews for editing and feedback.

The banner image was created using Lasse Dybdahl's original work. It is subsequently listed under the Creative Commons 4.0 license.

This story will be part of a series of speculative fiction works by friends, all similarly positioned as attempts to imagine the future of climate change and the CCC. Follow me on twitter for updates about subsequent releases in the series.